CHAPTER VI

WHITBY

'Behold the glorious summer sea

As night's dark wings unfold,

And o'er the waters, 'neath the stars,

The harbour lights behold.'

E. Teschemacher.

|

Despite a huge influx of summer visitors, and despite the modern town

which has grown up to receive them, Whitby is still one of the most

strikingly picturesque towns in England. But at the same time, if one

excepts the abbey, the church, and the market-house, there are scarcely

any architectural attractions in the town. The charm of the place does

not lie so much in detail as in broad effects. The narrow streets have

no surprises in the way of carved-oak brackets or curious panelled

doorways, although narrow passages and steep flights of stone steps

abound. On the other hand, the old parts of the town, when seen from a

distance, are always presenting themselves in new apparel.

|

|

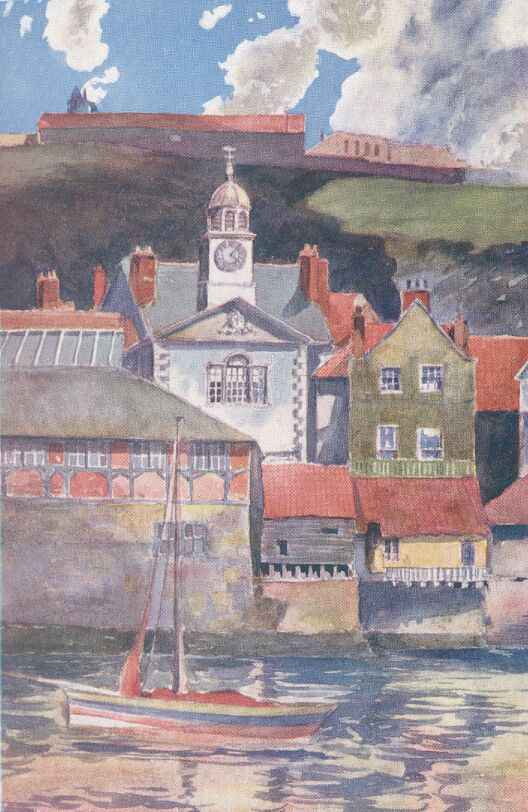

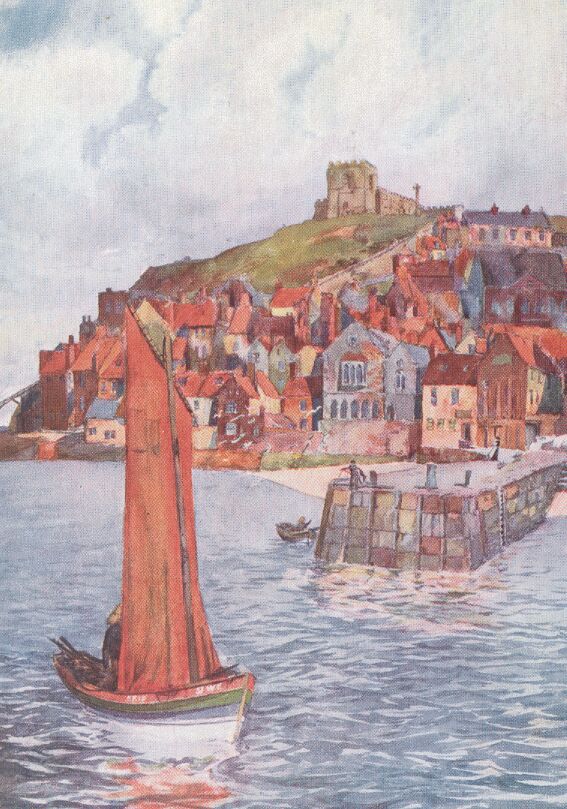

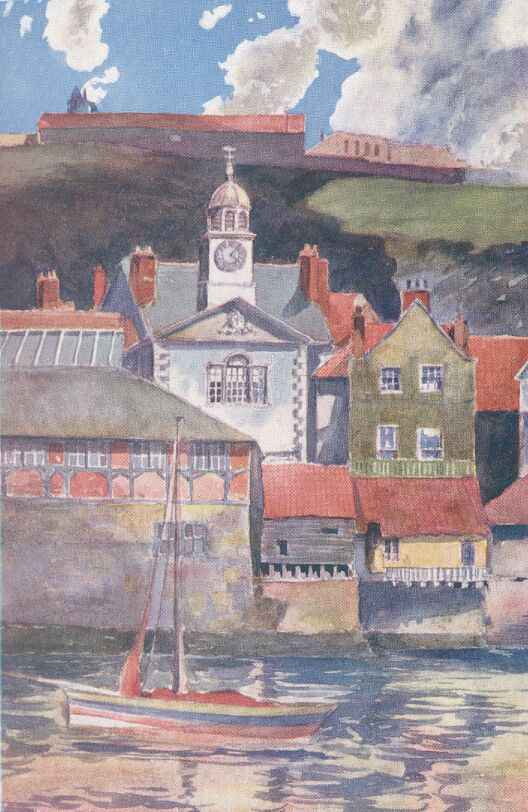

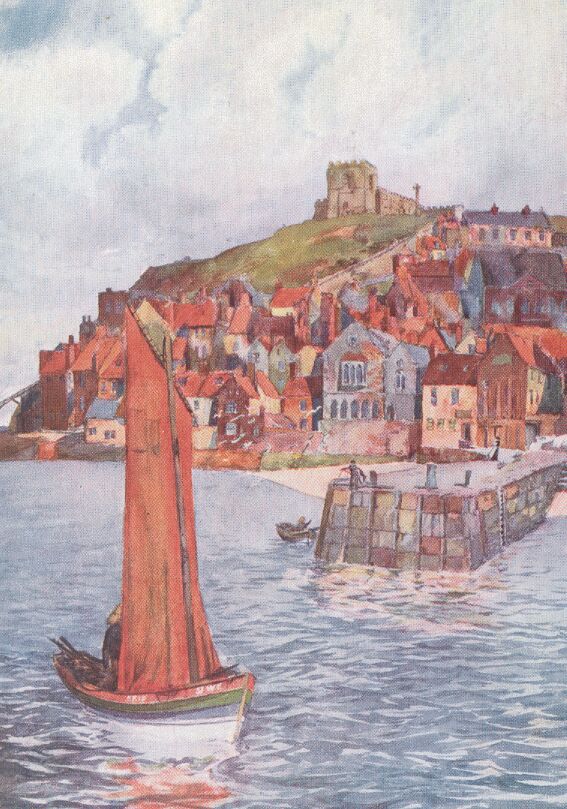

In the early morning the East Cliff generally appears merely as a pale

gray silhouette with a square projection representing the church, and a

fretted one the abbey. But as the sun climbs upwards, colour and

definition grow out of the haze of smoke and shadows, and the roofs

assume their ruddy tones. At mid-day, when the sunlight pours down upon

the medley of houses clustered along the face of the cliff, the scene is

brilliantly coloured. The predominant note is the red of the chimneys

and roofs and stray patches of brickwork, but the walls that go down to

the water's edge are green below and full of rich browns above, and in

many places the sides of the cottages are coloured with an ochre wash,

while above them all the top of the cliff appears covered with grass. On

a clear day, when detached clouds are passing across the sun, the houses

are sometimes lit up in the strangest fashion, their quaint outlines

being suddenly thrown out from the cliff by a broad patch of shadow upon

the grass and rocks behind. But there is scarcely a chimney in this old

part of Whitby that does not contribute to the mist of blue-gray smoke

that slowly drifts up the face of the cliff, and thus, when there is no

bright sunshine, colour and detail are subdued in the haze.

In many towns whose antiquity and picturesqueness are more popular than

the attractions of Whitby, the railway deposits one in some

distressingly ugly modern excrescence, from which it may even be

necessary for a stranger to ask his way to the old-world features he has

come to see. But at Whitby the railway, without doing any harm to the

appearance of the town, at once gives a visitor as typical a scene of

fishing-life as he will ever find. When the tide is up and the wharves

are crowded with boats, this upper portion of Whitby Harbour is at its

best, and to step from the railway compartment entered at King's Cross

into this busy scene is an experience to be remembered.

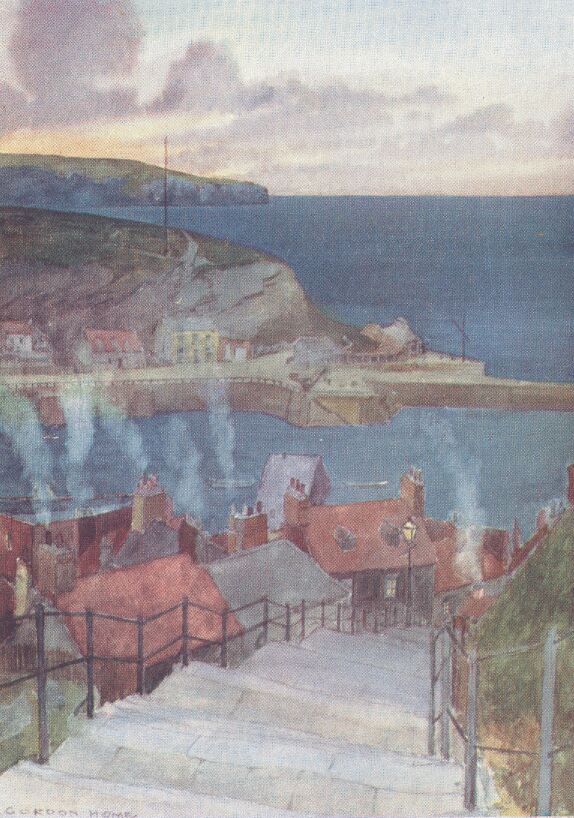

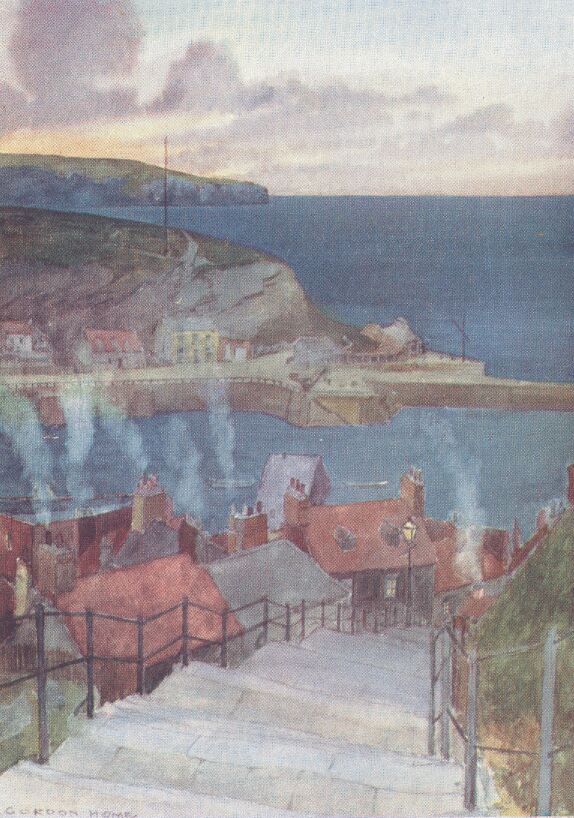

In the deepening twilight of a clear evening the harbour gathers to

itself the additional charm of mysterious indefiniteness, and among the

long-drawn-out reflections appear sinuous lines of yellow light beneath

the lamps by the bridge. Looking towards the ocean from the outer

harbour, one sees the massive arms which Whitby has thrust into the

waves, holding aloft the steady lights that

'Safely guide the mighty ships

Into the harbour bay.'

If we keep to the waterside, modern Whitby has no terrors for us. It is

out of sight, and might therefore have never existed. But when we have

crossed the bridge, and passed along the narrow thoroughfare known as

Church Street to the steps leading up the face of the cliff, we must

prepare ourselves for a new aspect of the town. There, upon the top of

the West Cliff, stand rows of sad-looking and dun-coloured

lodging-houses, relieved by the aggressive bulk of a huge hotel, with

corner turrets, that frowns savagely at the unfinished crescent, where

there are many apartments with 'rooms facing the sea.' The only

redeeming feature of this modern side of Whitby is the circumscribed

area it occupies, so that the view from the top of the 199 steps we have

climbed is not altogether vitiated. A distinctive feature of the west

side of the river has been lost in the sails of the Union Mill, which

were taken down some years ago, and the solid brick building where many

of the Whitby people, by the excellent method of cooperation, obtained

their flour at reduced prices is now the headquarters of some

volunteers.

The town seems to have no idea of re-erecting the sails of the windmill,

and as I have so far heard of no scheme for demolishing the

unpleasant-looking houses on the West Cliff, we will shut our eyes to

these shortcomings, and admit that the task is not difficult in the

presence of such a superb view over Whitby's glorious surroundings. We

look over the chimney-stacks of the topmost houses, and see the silver

Esk winding placidly in the deep channel it has carved for itself; and

further away we see the far-off moorland heights, brown and blue, where

the sources of the broad river down below are fed by the united efforts

of innumerable tiny streams deep in the heather. Behind us stands the

massive-looking parish church, with its Norman tower, so sturdily built

that its height seems scarcely greater than its breadth. There is surely

no other church with such a ponderous exterior that is so completely

deceptive as to its internal aspect, for St. Mary's contains the most

remarkable series of beehive-like galleries that were ever crammed into

a parish church. They are not merely very wide and ill-arranged, but

they are superposed one above the other. The free use of white paint all

over the sloping tiers of pews has prevented the interior from being as

dark as it would have otherwise been, but the result of all this painted

deal has been to give the building the most eccentric and indecorous

appearance. Still, there are few who will fail to thank the good folks

of Whitby for preserving an ecclesiastical curiosity of such an unusual

nature. The box-pews on the floor of the church are separated by very

narrow gangways—we cannot call them aisles—and the gallery across the

chancel arch is particularly noticeable for the twisted wooden columns

supporting it. Various pews in the transepts and elsewhere have been

reserved for many generations for the use of people from outlying

villages, such as Aislaby, Ugglebarnby, and Hawskercum-Stainsacre, and

it was this necessity for accommodating a very large congregation that

taxed the ingenuity of the churchwardens, and resulted in the strange

interior existing to-day.

The early history of Whitby from the time of the landing of Roman

soldiers in Dunsley Bay seems to be very closely associated with the

abbey founded by Hilda about two years after the battle of Winwidfield,

fought on November 15, A.D. 654; but I will not venture to state an

opinion here as to whether there was any town at Streoneshalh before the

building of the abbey, or whether the place that has since become known

as Whitby grew on account of the presence of the abbey. Such matters as

these have been fought out by an expert in the archaeology of

Cleveland—the late Canon Atkinson, who seemed to take infinite pleasure

in demolishing the elaborately constructed theories of those painstaking

historians of the eighteenth century, Dr. Young and Mr. Lionel Charlton.

Many facts, however, which throw light on the early days of the abbey

are now unassailable. We see that Hilda must have been a most remarkable

woman for her times, instilling into those around her a passion for

learning as well as right-living, for despite the fact that they worked

and prayed in rude wooden buildings, with walls formed, most probably,

of split tree-trunks, after the fashion of the church at Greenstead in

Essex, we find the institution producing, among others, such men as Bosa

and John, both Bishops of York, and such a poet as Caadmon. The legend

of his inspiration, however, may be placed beside the story of how the

saintly Abbess turned the snakes into the fossil ammonites with which

the liassic shores of Whitby are strewn. Hilda, who probably died in the

year 680, was succeeded by Aelfleda, the daughter of King Oswin of

Northumbria, whom she had trained in the abbey, and there seems little

doubt that her pupil carried on successfully the beneficent work of the

foundress.

Aelfleda had the support of her mother's presence as well as the wise

counsels of Bishop Trumwine, who had taken refuge at Streoneshalh, after

having been driven from his own sphere of work by the depredations of

the Picts and Scots. We then learn that Aelfleda died at the age of

fifty-nine, but from that year—probably 713—a complete silence falls

upon the work of the abbey; for if any records were made during the next

century and a half, they have been totally lost. About the year 867 the

Danes reached this part of Yorkshire, and we know that they laid waste

the abbey, and most probably the town also; but the invaders gradually

started new settlements, or 'bys,' and Whitby must certainly have grown

into a place of some size by the time of Edward the Confessor, for just

previous to the Norman invasion it was assessed for Danegeld to the

extent of a sum equivalent to £3,500 at the present time.

After the Conquest a monk named Reinfrid succeeded in reviving a

monastery on the site of the old one, having probably gained the

permission of William de Percy, the lord of the district. The new

establishment, however, was for monks only, and was for some time

merely a priory.

The form of the successive buildings from the time of Hilda until the

building of the stately abbey church, whose ruins are now to be seen, is

a subject of great interest, but, unfortunately, there are few facts to

go upon. The very first church was, as I have already suggested, a

building of rude construction, scarcely better than the humble dwellings

of the monks and nuns. The timber walls were most probably thatched, and

the windows would be of small lattice or boards pierced with small

holes. Gradually the improvements brought about would have led to the

use of stone for the walls, and the buildings destroyed by the Danes

probably resembled such examples of Anglo-Saxon work as may still be

seen in the churches of Bradford-on-Avon and Monkwearmouth.

The buildings erected by Reinfrid under the Norman influence then

prevailing in England must have been a slight advance upon the destroyed

fabric, and we know that during the time of his successor, Serlo de

Percy, there was a certain Godfrey in charge of the building operations,

and there is every reason to believe that he completed the church during

the fifty years of prosperity the monastery passed through at that time.

But this was not the structure which survived, for towards the end of

Stephen's reign, or during that of Henry II., the unfortunate convent

was devastated by the King of Norway, who entered the harbour, and, in

the words of the chronicle, 'laid waste everything, both within doors

and without.' The abbey slowly recovered from this disaster, and if any

church were built on the ruins between 1160 and the reconstruction

commenced in 1220, there is no part of it surviving to-day in the

beautiful ruin that still makes a conspicuous landmark from the sea.

It was after the Dissolution that the abbey buildings came into the

hands of Sir Richard Cholmley, who paid over to Henry VIII. the sum of

£333 8s. 4d. The manors of Eskdaleside and Ugglebarnby, with all 'their

rights, members and appurtenances as they formerly had belonged to the

abbey of Whitby,' henceforward belonged to Sir Richard and his

successors. Sir Hugh Cholmley, whose defence of Scarborough Castle has

made him a name in history, was born on July 22, 1600, at Roxby, near

Pickering. He has been justly called 'the father of Whitby,' and it is

to him we owe a fascinating account of his life at Whitby in Stuart and

Jacobean times. He describes how he lived for some time in the

gate-house of the abbey buildings, 'till my house was repaired and

habitable, which then was very ruinous and all unhandsome, the wall

being only of timber and plaster, and ill-contrived within: and besides

the repairs, or rather re-edifying the house, I built the stable and

barn, I heightened the outwalls of the court double to what they were,

and made all the wall round about the paddock; so that the place hath

been improved very much, both for beauty and profit, by me more than all

my ancestors, for there was not a tree about the house but was set in my

time, and almost by my own hand. The Court levels, which laid upon a

hanging ground, unhandsomely, very ill-watered, having only the low

well, which is in the Almsers-close, which I covered; and also

discovered, and erected, the other adjoining conduit, and the well in

the courtyard from whence I conveyed by leaden pipes water into the

house, brewhouse, and washhouse.'

In the spring of 1636 the reconstruction of the abbey house was

finished, and Sir Hugh moved in with his family. 'My dear wife,' he

says, '(who was excellent at dressing and making all handsome within

doors) had put it into a fine posture, and furnished with many good

things, so that, I believe, there were few gentlemen in the country, of

my rank, exceeded it.... I was at this time made Deputy-lieutenant and

Colonel over the Train-bands within the hundred of Whitby Strand,

Ryedale, Pickering, Lythe and Scarborough town; for that, my father

being dead, the country looked upon me as the chief of my family.'

Sir Hugh had been somewhat addicted to gambling in his younger days, and

had made a few debts of his own before he undertook to deal with his

father's heavy liabilities, and in the early years of his married life

he had been very much taken up with the difficult and arduous work of

paying off the amounts due to the clamorous creditors. During this

process he had been forced to live very quietly, and had incidentally

sifted out his real friends from among his relations and acquaintances.

Thus, it is with pardonable pride that he says: 'Having mastered my

debts, I did not only appear at all public meetings in a very

gentlemanly equipage, but lived in as handsome and plentiful fashion at

home as any gentleman in all the country, of my rank. I had between

thirty and forty in my ordinary family, a chaplain who said prayers

every morning at six, and again before dinner and supper, a porter who

merely attended the gates, which were ever shut up before dinner, when

the bell rung to prayers, and not opened till one o'clock, except for

some strangers who came to dinner, which was ever fit to receive three

or four besides my family, without any trouble; and whatever their fare

was, they were sure to have a hearty welcome. Twice a week, a certain

number of old people, widows and indigent persons, were served at my

gates with bread and good pottage made of beef, which I mention that

those which succeed may follow the example.' Not content with merely

benefiting the aged folk of his town, Sir Hugh took great pains to

extend the piers, and in 1632 went to London to petition the

'Council-table' to allow a general contribution for this purpose

throughout the country. As a result of his efforts, 'all that part of

the pier to the west end of the harbour' was erected, and yet he

complains that, though it was the means of preserving a large section of

the town from the sea, the townsfolk would not interest themselves in

the repairs necessitated by force of the waves. 'I wish, with all my

heart,' he exclaims, 'the next generation may have more public spirit.'

Sir Hugh Cholmley also built a market-house for the town, and removed

the bridge to its present position. Owing to rebuilding, neither of

these actual works remains with us to-day, but their influence on the

progress of Whitby must have been considerable.

On a June morning in the year after Sir Hugh had settled down so

handsomely in his refurbished house, two Dutch men-of-war chased into

the harbour 'a small pickroon belonging to the King of Spain.' The

Hollanders had 400 men in one ship and 200 in the other, but the

Spaniard had only thirty men and two small guns. The Holland ships

proceeded to anchor outside the harbour, and, lowering their longboats,

sent ashore forty men, all armed with pistols. But the Spaniards had

been on the alert, and having warped their vessel to a safer position

above the bridge, they placed their two guns on the deck, and every man

prepared himself to defend the ship.

'I, having notice of this,' writes Sir Hugh, 'fearing they might do here

the like affront as they did at Scarborough, where they landed one

hundred men, and took a ship belonging to the King of Spain out of the

harbour, sent for the Holland Captains, and ordered them not to offer

any act of hostility; for that the Spaniard was the King's friend, and

to have protection in his ports. After some expostulations, they

promised not to meddle with the Dunkirker [Spaniard] if he offered no

injury to them; which I gave him strict charge against, and to trust to

the King's protection. These Holland Captains leaving me, and going into

the town, sent for the Dunkirk Captain to dine with them, and soon after

took occasion to quarrel with him, at the same time ordered their men to

fall on the Dunkirk ship, which they soon surprised, the Captain and

most of the men being absent. I being in my courtyard, and hearing some

pistols discharged, and being told the Dunkirker and Hollanders were at

odds, made haste unto the town, having only a cane in my hand, and one

that followed me without any weapon, thinking my presence would pacify

all differences. When I came to the river-side, on the sand between the

coal-yard and the bridge, I found the Holland Captain with a pistol in

his hand, calling to his men, then in the Dunkirk ship, to send a boat

for him. I gave him good words, and held him in treaty until I got near

him, and then, giving a leap on him, caught hold of his pistol, which I

became master of; yet not without some hazard from the ship, for one

from thence levelled a musket at me; but I espying it, turned the

Captain between me and him, which prevented his shooting.'

When Sir Hugh had secured the Captain, he sent a boatload of men to

retake the ship, and as soon as the Hollanders saw it approaching, they

fled to their own vessels outside the harbour. In the afternoon Sir Hugh

intercepted a letter to his prisoner, telling him to be of good cheer,

for at midnight they would land 200 men and bring him away. This was a

serious matter, and Sir Hugh sent to Sir John Hotham, the High Sheriff

of the county, who at once came from Fyling, and summoned all the

adjacent train-bands. There were about 200 men on guard all through the

night, and evidently the Hollanders had observed the activity on shore,

for they made no attack. The ships continued to hover outside the

harbour for two or three days, until Sir Hugh sent the Captain to York.

He was afterwards taken to London, where he remained a prisoner, after

the fashion of those times, for nearly two years.

It was after the troublous times of the Civil War that Sir Hugh

re-established himself at Whitby, and opened a new era of prosperity for

himself and the townsfolk in the alum-works at Saltwick Nab.